MORPHOLOGY

Modern English is considered a Germanic language just as Old English was as well. English today is considered the most Latinized of the Germanic languages because in the vocabulary of trade and science some figures estimate that up to ninety percent are borrowed from Latin and that possibly sixty percent of the stems of words have Latin or Ancient Greek origins overall. However, in the day-to-day words as well as in the structure of the English syntax, English today remains Germanic in structure.

In all of the traditional books of study on Old English and even in the modern ones, the authors all begin explanations of morphology with nouns and verbs. Old English had grammatical gender (including neuter) as well as case marker, quantity and gender agreement. It is also important to know that in Germanic languages one will read of strong and weak declensions and inflections. A strong declension (in the case of nouns) refers to words which decline irregularly rather than by suffixation. This always has to do with vocalic sounds and with what syllable these sounds occur in. This would occur with the example of singular “goose” and its plural “geese” because these declensions are considered irregular even by irregular standards. The term weak tends to be compared to being the regular form in which a word declines, or in the case of weak verbs, a regular inflection. With strong verbs, the conjugations occur when there is the ablaut vowel shift in the stem of the verb (such as the shifts that occur from the present/infinitive to the past-preterit drive/drove, sing/sang. Strong and weak declensions always go together and are not the same as irregular or regular changes in a word. With verbs what ends up happening is that there are two verbs which mean the same thing but are slightly different and depending on one of them fitting the irregular declension criteria, this makes one “strong” and the other word in the set is mostly regular. Some examples in English are the verbs come/came, fall/fell, give/gave. Depending on the vernacular of English one speaks, it might appear that one of the verbs in these sets is a past tense form of the infinite which is true in some dialects but in many others it is the opposite (another example is lay/lie). In Old English there are seven types of strong verbs and examples of this will be shown further on. With regard to case, Old English had in total six cases (nominative, accusative, dative, genitive and locative in the Northumbrian dialect) but the information here will depict the four main cases by a capital N, A, D, G or I (which in the West Saxon Old English that most texts reference usually is the same as the dative).

.

C. Alphonso Smith in 1896 had observed from primary sources of Old English that -a noun declension from early on in Old English replaced the -i,-u forms of masculine and neuter noun declensions. Richard Hogg more recently has spoken of how flawed Old English grammar was as well and named many types of declension that replaced other ones or that were used in lieu of the correct forms and what this tells me is that the information being recorded as Old English grammar isn’t flawed at all; it is the authors who pen grammar that are flawed . When one considers that kings and monks were the ones that recorded a language, it is likely that what they have recorded as the norms of language are not the ways that the people spoke.

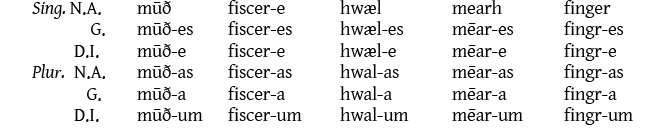

Observations in the above diagram of Image Number 9 are that nouns with the -e in the nominative ending drop it before adding the case ending and æ before a consonant turns into a. The above example illustrates the declination of the stem but it does not show how the article, or determiner also changes respective to quantity, gender and case (it should be noted that in this project dual pronouns and dual grammatical forms are not explained nor shown but that they were used in Old English as singular concepts for things that were of two or more entities and later on reserved for quantities of three or more in personal pronouns which is what many Germanic languages still do).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_English_grammar

Image Number 10

The above chart has the Modern English equivalents so one can understand the meaning using the different cases. Now, if I take the noun “fiscere” from above and add the correct articles to the different cases it looks like this:

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | se fiscere | þā fisceras |

| Accusative | þone fiscere | þā fisceras |

| Genitive | þæs fisceres | þāra fiscera |

| Dative | þǣm fiscere | þǣm fiscerum |

| Instrumental | þȳ fiscere | þǣm fiscerum |

Table by Alina Fernanda Picayo

Image Number 11

It is important to reiterate that the above examples are of the most common masculine noun declension and that it seems that in Old English works authors mention much of the confusion in spoken Old English. This has been a constant theme in the works of C. Alphonso Smith from the later 1800s and is mentioned by Millward and Hayes in A Biography of the English Language which was published over a hundred years after and reads

That native speakers of OE were not themselves always sure of the correct gender is evidenced by the fact that many OE nouns are recorded with two different genders and a few with all three: gyrn ‘sorrow’ is both masculine and neuter; sunbe¯am ‘sunbeam’ is both masculine and feminine; su¯sl ‘misery’ is both neuter and feminine; and we¯sten ‘wilderness’ may be masculine, feminine, or neuter.

(A Biography of the English Language, Milward & Hayes 102)

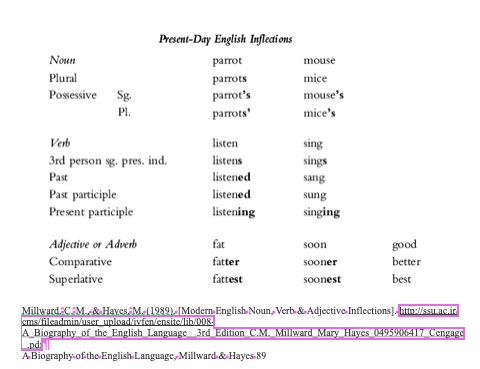

Now, in this chart below one can observe how different these inflections and declensions are today in Modern English.

Just in looking at the nouns at the top of the chart we see that all trace of grammatical gender is gone and that the only case marker distinguishable by its orthography is the genitive, or possessive form for singular and plural. The determiners left behind no longer indicate case, number nor gender as they are “the”, “that”, except in the case of “these” or “those” where their meaning as determiners is used for plural nouns. This loss of declension in nouns, case makers and articles on a whole has resulted in a very rigid order of words in Modern English in order to convey one’s exact meaning because there is no longer a distinct way to indicate the function of the noun or its coordinating adjective (which also matched the noun it was describing for case, number and gender) inside of a sentence. If I gave the two nouns, “the dog” and “the house” in Modern English and asked you which was the indirect object in side of the sentence “(The blank noun 1) is next to (The blank noun 2)” of those two noun choices, you could say either and you’d be simultaneously wrong and right because you simply do not know. All you would know is that both options are singular nouns and nothing else. The same goes if I asked you to then attach a feminine singular adjective and a masculine singular adjective to the corresponding noun because there is no way to label any of that information to the current system of English which makes strict word order essential.

Let’s look at some verbs. Speaking of contractions like “let’s” or “let us”, in Old English these were not used. This only appeared in writing in and or around the seventeenth century A.D. in Modern English. We spoke of strong verbs and weak verbs are being parts of a parallel system of existence. Basically, verbs were either strong or weak or just considered other verbs.

The above chart represents the seven types of irregularly irregular verbs (strong verbs) and below each class number are the vocalic inflections found for each class. This wasn’t as simple as just looking at a certain type of ending in written form and conjugating according to some silly rules. These classes of inflections were based on phonology and the spoken word and there is always a lot of irregularity of usage or verbs being inflected like a different class depending on where you lived and what dialect of English you spoke. All speakers of the language understood one another but just like it still is today, no pronunciation was alike, and some verbs fared better when they were conjugated as weak verbs (following regular rules) because just as in physics one speaks of movement following the path of least resistance, so too does sound when we produce it. Within this chart, this is further demonstrated by the amount of irregularities found in some classes such as class 3 verbs. Many classes underwent sound mutations and perhaps morphed a lot or ended up becoming weak verbs. It is important to always keep in mind that in a very short period of time many different languages and their people were thrown together, sharing a relatively small island and that in order to keep peace among these many groups, there was a lot of mixing of language and non-native speakers speaking each other’s languages. There were Celtic, Norse and Anglo-Saxon languages being mixed and over time certain borrowings of Latin, Norse and Celtic words likely affected inflectional changes of verbs. English today is a language of having to learn verbs individually as there aren’t three types of endings to learn. I am convinced that English even in the Old English days was a language where verbs were inflected differently in different places and that everyone still understood what you were saying. It might be considered proof of this when one sees class 7 verb slæpan (to sleep) which has survived up until today with the past tense form which ended up becoming the regular past tense (by adding suffix -ed to make sleeped as well as the strong form of the verb today, slept). Interestingly, the verbs “to dream” and “to sleep” are considered to be the same in verb form, some sources listing the past tense of “to sleep” as gemæ (the ge- is still used in Germanic languages when indicating simple past tense) although there is a noun form of “dream” that is different but when one looks at how all of these changes have turned out today you still find “to sleep” and “to dream” in the same boat of having each a Modern English weak and strong form (suffix -ed and -t). Of course today, all prefixes of the simple past tense -ge are obsolete.

Here is a great list of verbs and conjugations I found on a Wikipedia site for verbs of Old English:

Of the hundreds of verbs from Old English, those that are still used today have a tendency of having once been strong nouns (some of those still in use have become weak verbs since). In Some of these strong verbs have changed over time but of the strong classes it is the class 3 verbs which have remained the most similar to their Old English forms, such as begin, run, drink, sing, and find. Overall, the verbs from Old English that have survived into Modern English are the most commonly used verbs and the ones one would learn in life from very early on.

In terms of these other verbs, only “to be” will be mentioned. This verb is not considered a strong or weak verb although it did have two forms, the infinitive bēon and the infinitive wesan, which expressed different states of permanence like ser and estar in Spanish.

Today there is only one “to be” verb used and it is one of the most irregular verbs in the English vocabulary, where some inflections have been plucked out and kept around to form the verb conjugations we know. We still use -eom (am), eart (which became art which then became are) and waes (was) but overall many of the inflections of bēon have been made obsolete from Old English. Similar processes underwent the anomalous verbs for “to do”, “to know” and “to go”. These verbs that have combined conjugations of two other anomalous forms to form one in English today and are irregular are called Preterite-Present Verbs. An inflection that has since been lost with these Preterite-Present Verbs is that of negation. With the verb wītan (“to know” which is also cunnan in its weak form) one could make the verb “to not know” by prefixing with ny- and making nytan (“to not know”). Many other verbs have since been lost as verbs which stand alone in English today and those are the verbs which today function as auxiliary modals such as should, shall, might, could, can and a few more. These now survive for making different complex construction including making a future tense when using the auxiliary modal “will.” In Old English you will only find conjugations of the present and past.